Overview of MOOC Recognition

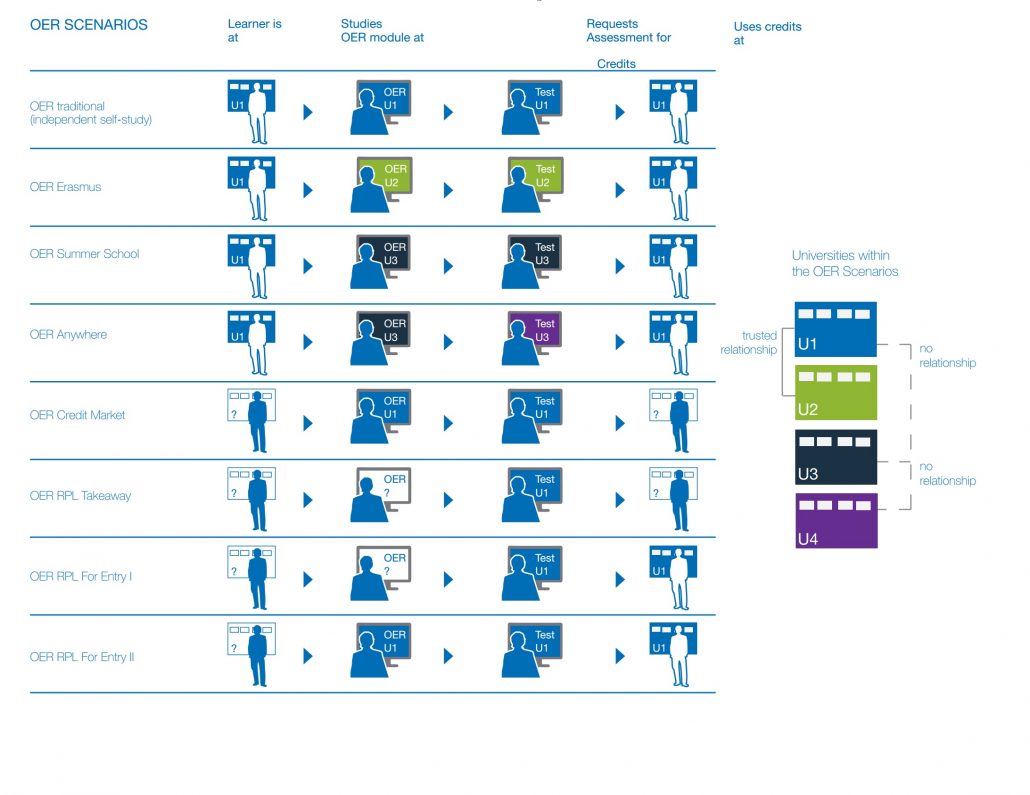

In Open Learning Recognition, Camilleri & Tannhauser proposed a set of scenarios for the recognition of credits based on open educational resources and MOOCs:

In the above diagram;

U1 is the university considering formally recognizing a MOOC i.e. the one to which the learner goes to request credits or to use credits from elsewhere.

• U2 is a university with which U1 has worked on an agreement regarding MOOC materials and assessment, and that is “trusted” by U1 to be of sufficient quality for its educational outcomes to be accepted by U1.

• U3 & U4 are universities with no links to U1 and the educational outcomes of which are unknown/not yet evaluated.

• ? is a location or organisation which is not a university or university-equivalent accredited provider. It may be the current or future employer of a learner, or the provider of online learning materials. For

example a museum or a non-governmental organisation might provide open online curricula or MOOCs.

The eight scenarios enable any university to understand the range of options that it faces when considering opening up its course and accreditation processes to open learning of this type, and enable it to make decisions as to which routes it is prepared to work with and which are not acceptable to it. It can also decide whether some are not possible due to legislation or other regulations and which routes are feasible.

Eight Scenarios for MOOC Recognition

Traditional

This scenario may be the least challenging for a university. If it places a MOOC online for general access, and those materials are sufficient in scope and quality of content and required associated activities to enable a learner to acquire the competences defined in the expected learning outcomes, and if the university is able to assess the competences, then credit may be easily awarded.

In the traditional scenario, the normal university QA processes can be applied to both the curriculum (the materials and educational design) and the assessment. This is due to the fact that the curriculum is designed by academic staff of the university accrediting the student’s learning. Although the learning process is independent of teaching staff, assessment is done by them, according to their definition of the expected learning outcomes set at the time the MOOC was released.

Erasmus

The Erasmus student exchange programme is predicated upon trust relationships between European universities, supported significantly by the Bologna Process and the ECTS credit system. Under this system, if a university is able to determine equivalency between the offerings of a partner institution and its own, and recognises the partner university’s assessment as valid, then it will allow its students to earn those credits at the partner institution, and recognise them as if it had awarded them itself.

These arrangements are formalised by means of Erasmus agreements between institutions, which can be broad-ranging for many students or individualised on an ad hoc basis.

In this scenario, students studying MOOCs can be seen as participating in virtual exchanges, applying the same rules that Erasmus exchanges have. Thus, the ‘home’ university must be assured of the quality of the MOOC that a student will study – a process which would be codified in agreements similar to Erasmus agreements.

Summer School

The Summer School scenario goes a step further than OER Erasmus, because in this case although the learner is a current student at U1, s/he has decided to study and gain ECTS credits from a university with no relationship with her/his current university U1. Although students may well do this sort of independent study to enhance their CVs or gain what they see as useful skills and knowledge, normally this type of study would not be credited towards the degree for which they are studying.

If such a situation arose, and credit was requested, a post hoc evaluation would be needed to determine whether the work was suitable and appropriate for inclusion in the degree programme and the standard was acceptable. Ideally, the learner would agree on such a process in advance. The mechanism to approve or refuse credits might be very similar to that used to Recognise Prior Learning.

Anywhere

The OER Anywhere scenario is a variant of OER Summer School, except that the evaluation of the learning that has taken place is more challenging than the one for U1 because the learning and the assessment have taken place at different universities, neither of which has a trust relationship with U1. Therefore, the U1 needs to assess the quality of both components to reach a decision on whether or not to recognise the credits gained.

Credit Market

U1 assesses the learner using the methods it has decided are appropriate for its own MOOC and offers ECTS credits to be taken away and used as the learner wishes/ is able to use. The parallel in traditional university education would be Continuing Professional Development / Education (CPD/CPD) where individual modules are studied without enrolment into a degree programme.

This scenario poses the biggest challenge to the university traditional QA processes, because the learner is neither a student of the university nor wishing to become one, but is solely interested in gaining academic credits. Setting aside the question of whether a university would wish to carry out this role, the challenges to the traditional QA processes are substantial. The award of credits to an individual assumes rigor in their identity, in the authenticity of their work and their participation in essential course components that may not be assessed formally but do contribute to the achievement of learning outcomes.

For students taking a whole degree, acceptance of some elements where this is less rigorously monitored is reasonable as long as the extent of these is limited. The quality of a year-long or multi-yearlong programme ensures that there is confidence in the overall quality of graduates and hence the university’s reputation (and indeed licence to award degrees) is not compromised. Traditional university QA processes are generally not designed to accommodate models where staff of the university are not closely involved in the process, and so in these scenarios, universities may wish to revert to an RPL mode to evaluate the learning themselves to be assured that the rigour and quality are correct. (This is reminiscent of the franchising of awards by some universities, whereby they set the curriculum but the teaching and assessment are carried out by staff at another university at which the learners are current students. This QA role by the franchising university requires a different QA model to the traditional ‘in-house QA’ model and has run into difficulties on many occasions.)

One model of operation in the OER Credit Market models is for an institution to specify the attributes of ‘acceptable’ curricula with which it is prepared to engage, thus removing a substantial element of diversity from the experiences learners might offer. In the extreme it might specify exactly which curricula (‘only OCW in Subject Y from University of X’) it will consider. Alternatively, it could define programmes of rigorous assessments in various subjects at one or more levels, and leave it to learners to gain the competences as they see fit (SATS or driving test model). By definition, these will tend to be examination oriented approaches and hence will eliminate a wide range of subjects and levels that cannot be effectively assessed in this way. The quality assurance task then resolves to ensuring rigour in the identification of learners (‘who they really are’) and in assessments and quality control of marking (‘what they really know’).

RPL Takeaway

Universities have used Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) to varying extents to enable entry to degree programmes of students whose background does contain suitable academic study for automatic entry. Although less common, there could also be cases where learners wish to get recognition of prior learning for purposes other than to enter a study programme. The former it is most common where employment experiences are being offered, especially to a professionally relevant degree programme such as Nursing or Law. Thus, the same mechanisms in terms of assessment of the competences of the intending student and the quality assurance processes that ensure its rigour could be applied. Where a fee is charged, this too might be applicable, with appropriate adjustment for the difficulty of the assessment. The openness to scrutiny of MOOC curricula may make the recognition easier.

Normally, credit is only given for a moderate proportion of the curriculum if recognition is given at all. The incentive for University 1 is that it gains a student, and access to HE is widened to those from a non-traditional background. The intending student will still have to participate in normal university studies, with the costs and benefits that this entails.

In the RPL scenario the problem of assessing the knowledge and skills of the learner presenting for evaluation is little different to that which has to take place if their learning has been based at work, at home or in other non-educational settings. A mapping has to be made of their competences (level, extent, domain of study) onto the curriculum they wish to enter, with credit awarded and attendance at specific courses recognised. As already mentioned, in some respects, MOOCs make this evaluation simpler than it would be for many work-based or non-formal learning experiences. It is clear that there is more variation between partner universities in their RPL practices, and the degree to which they employ it as a route to entry to their degree programmes. In general, RPL lies in a different ‘area’ of QA to the normal academic curriculum and progression, and has a significant ‘ad hoc’ element which is not surprising given the diversity of learning situations that RPL brings forward. In this respect, the inherent flexibility of ‘traditional RPL’ should signal the potential for MOOCs, should a university wish to follow this route.

RPL for Entry

To enable learners who have studied using open learning materials to enter a university, some form of recognition of prior learning will normally be required. If the learner is able to explicitly prove that a specific set of learning outcomes has been assessed in the MOOC, the burden of RPL will be much reduced. The case in which the open learning materials offered by the university are also required for entry (i.e. U1 in our RPL II scenario) is even simpler, as U1 knows that its MOOC is at the appropriate standard and level, and the ECTS credit-equivalence is clear. In RPL for Entry I, this is not the case, so some form of additional assessment or evaluation may well be required.

Kiron is not a recognized university in Germany and does not award degrees. However, 53 partner universities in Germany and other countries currently allow Kiron students to transfer into their degree programs, usually after completion of four semesters of study at Kiron, which studies are powered by MOOCs.